Obituaries

Mimi Jones, civil rights activist in a historic St. Augustine swim-in, dies at 73

News article By Harrison Smith from July 29, 2020

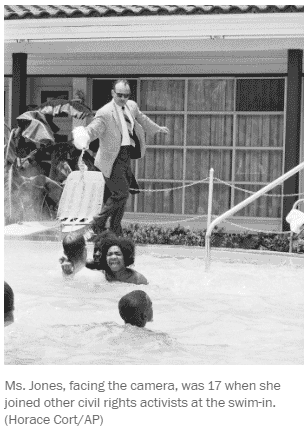

A day before the Senate voted to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Mimi Jones joined six other civil rights activists in leaping into a Whites-only motel pool in St. Augustine, Fla. Moments later, the motel’s manager emerged with a jug of muriatic acid, a cleaning agent, and poured it into the water.

“I’m cleaning pool!” he yelled.

Diluted by the water, the acid irritated Ms. Jones’s face and eyes but otherwise left the protesters unharmed. And as a White crowd cheered nearby — “Arrest them! Get the dogs!” — an out-of-uniform police officer dove into the water, wearing everything but his shoes.

Ms. Jones and her fellow swimmers were hauled off to jail, along with a group of more than 40 other civil rights protesters, including 16 rabbis, who had tried to dine at the Monson Motor Lodge’s Whites-only restaurant.

“We would not have had the decisive victory that we had in the ’64 Civil Rights Act if we had not been in St. Augustine,” activist, politician and diplomat Andrew Young said in an interview for the 2015 documentary “Passage at St. Augustine.”

The legislation was passed on the same day that photos of the swim-in appeared on the cover of The Washington Post, the New York Times and other newspapers around the world. Some showed Ms. Jones, mouth open in horror, moving toward the center of the pool as the manager, James Brock, stood nearby pouring acid.

Ms. Jones was 73 when she died July 26 at her home in the Roxbury section of Boston, where she had spent the last years of her life championing literacy efforts and working as a grant writer for nonprofit organizations. Her son, Gervase Jones, confirmed the death but did not give a precise cause.

At age 17, Ms. Jones — then known as Mamie Ford — was one of the youngest protesters to put her body on the line in St. Augustine. But she was already a veteran of the struggle for racial equality, a Georgia native who had joined the Albany Movement two years earlier to protest segregation and discrimination near her hometown.

“I can’t remember how many times she was arrested,” her younger sister, fellow activist Altomease Ford Latting, said in a phone interview. “She was a fireball. I think if it wasn’t for Mamie’s conviction for social justice, I don’t know if I would have been involved with civil rights. . . . As [civil rights activist] Fannie Lou Hamer said, we had just gotten sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Ms. Jones taught elderly, uneducated Black residents how to read, so they could register to vote at a time when Georgia and other Southern states imposed literacy tests to limit access to the ballot box. Once, while she was working on voter registration in a segregationist stronghold known as “Terrible Terrell County,” Klansmen encircled the home where she and her sister were meeting with other activists.

“The next thing we knew, one of those homemade bombs came through the picture window,” Latting said. “No one was hurt, but we were very much frightened. My eyes and Mamie’s eyes became as big as saucers. We were so afraid that we had to get escorts back to Albany.”

A charismatic public speaker, confident beyond her years, Ms. Jones traveled the country as a spokeswoman for the civil rights movement, raising money for the 1963 March on Washington. A year later, she heeded the call when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference sought additional volunteers in St. Augustine, known as the nation’s oldest city.

For weeks, demonstrators marched at night to the Old Slave Market, amid counterprotests from the Klan. On the beach, according to the King biography “Let the Trumpet Sound,” “roving gangs whipped Negro bathers with chains and almost drowned C.T. Vivian,” the King field general who died earlier this month.

Organizers developed a plan to hold a swim-in at the Monson Motor Lodge, where many of the out-of-town journalists stayed and where King had been arrested for trying to dine. Brock, the manager, was also the president of the Florida Hotel and Motel Association.

But according to Nolan, practically none of the civil rights activists knew how to swim — leading Hosea Williams, a member of King’s inner circle, to say he “knew some people in Georgia who knew how to swim.” That group included Ms. Jones, who had learned to swim at a creek near her home.

On June 18, 1964, she jumped out of a car, hopped over a hedge and stepped into the Monson pool, accompanied by five Black activists and two White colleagues who had registered at the motel. “All of a sudden the water in front of my face started to bubble up, like a volcanic eruption,” she later told the Boston television station WGBH. “I could barely breathe. It was entering my nose and my eyes.”

King was watching from across the street and later described seeing police officers strike some of the civil rights activists with cattle prods and bludgeons. Also watching was Ms. Jones’s younger sister, then 14, who said she had planned to enter the pool as part of a “second wave” but was arrested after moving toward the scene.

Ms. Jones went on to spend about a week in jail. Upon her release she returned to Georgia, where she joined a group of six Black girls who desegregated all-White Albany High, where classrooms were outfitted with both American and Confederate flags and Black students were routinely mistreated, according to her sister.

“Whatever Mamie did, she didn’t do for herself, she did it for a cause,” said Latting, who enrolled at the high school herself the next year. “She always let it be known, whatever your gifts — and God had given her many talents and abilities — that your gifts are not to be kept to yourself. They are to be used for the benefit of the community.

“She was a fighter for the voiceless and the marginalized,” Latting continued. “She worked from the day she became an activist until the day she died.”

Mamie Nell Ford was born in Oakfield, Ga., a rural community just outside Albany, on May 4, 1947. The 13th of 14 children, she helped her parents on a 250-acre family farm, where she picked cotton, pulled peanuts and went into town on Saturdays to sell eggs and butter.

When her mother took a job as a maid, Mamie and Altomease moved with her into Albany. Their minister, the Rev. Samuel B. Wells, emerged as a leader of the Albany civil rights movement, introduced the teenage girls to the concept of nonviolent resistance and traveled with them to St. Augustine, quelling some of their parents’ concerns over safety, according to Latting.

Ms. Jones studied political science at the University of Massachusetts at Boston. After receiving a bachelor’s degree, she worked for the state education department and later became a grant writer for organizations including Veterans Benefits Clearinghouse, a social service agency.

In addition to her son, survivors include her husband of about 30 years, John Jones, and three sisters.

Ms. Jones returned to St. Augustine in 2014 accompanied by documentary filmmaker Clennon L. King, who featured her story in the movie “Passage at St. Augustine.” They visited the site of the demolished Monson motel, and Ms. Jones dipped her toes into the ocean, at a beach that had been blocked to her by a mob of angry Whites half a century earlier.

“I think she felt very unrecognized for a long time,” King said.

He added that Ms. Jones believed that “we must mark history or we’re condemned to repeat it.” She often cited an old proverb: “Until the lions have their own historians, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”